Despite Prior Decision Emphasizing Burden, ALJ Orders Google To Produce Extensive Pay Data Fields To OFCCP: Decision Narrows Scope of OFCCP's Request But Leaves In Place Tremendously Burdensome Information Demand

Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) Steven Berlin issued another ruling in the ongoing dispute between the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) and Google regarding the breadth and scope of pay data that OFCCP is seeking as part of its routine compliance review of Google's Mountain View, California headquarters. Despite employers' optimism that the ALJ's earlier decision would lead him to deny the bulk of OFCCP's requests on relevance or burden grounds, this latest decision grants OFCCP a large proportion of what it was seeking.

In the prior decision, the judge was asked whether to rule summarily for OFCCP and compel Google to turn over a substantial amount of pay data, or allow the dispute to proceed to a hearing. The ALJ previously ruled that OFCCP was not entitled to a summary decision, noting in part that it would be quite burdensome for Google to comply with OFCCP's requests. Google had only received $600,000 in contract payments, compared to costs in excess of $1,000,000 to extract the data from multiple systems. He ordered the parties to proceed to a hearing, where there could be testimony and evidence from both sides about the scope and relevance of the requests and the burden to Google, among other issues. This is the ruling that arises out of the hearing.

OFCCP was seeking extensive information based on preliminary indicators showing women were paid less that men. OFCCP's basis for much of its extensive data demand was its theory that women do not negotiate as hard as men do at the time of hire and thus Google's use of an applicant's current salary as a reference point in setting initial pay perpetuates gender discrimination. In this decision, the ALJ:

- Ordered Google to produce another snapshot on the approximately 19,000 employees at Google's headquarters' establishment from the year prior to the employee snapshot provided in Google's initial desk audit submission;

- Ordered that Google include in that snapshot approximately 50 data variables (which Google will have to pull from multiple different systems);

- Denied without prejudice OFCCP's request for salary and job histories, offering OFCCP the opportunity to renew the request if it can show that the request is reasonable, within its authority, related to the investigation, focused and not unduly burdensome, and ordering OFCCP to engage in meaningful, good faith conciliation with Google before renewing such a request; and

- Granted in large part OFCCP's request for home addresses, personal telephone numbers, and personal email addresses on employees across the two data snapshots, ordering Google to provide that data initially on 5,000 employees and perhaps another 3,000 in a second tranche, but not the full 25,000 employees that OFCCP was requesting. OFCCP can use that information to contact employees at home for the purpose of conducting interviews "in plain sight" of Google and without employees' fear of retaliation for talking to the OFCCP investigators.

Make no mistake about this decision – the relevance threshold for OFCCP to obtain a lot of data during its compliance review investigations remains very low. Despite repeated references in the ALJ's decision to burden, proportionality of requests to the dollar value of the employer's contracts, relevance of OFCCP's requests, and the contextual importance of the distinction between compliance reviews (which are not prompted by an allegation of discrimination) and complaints (which are), the ALJ nonetheless ordered Google to provide an incredibly broad amount of information to OFCCP based on the establishment of only a superficial basis (as found by the ALJ) for relevance and of need by OFCCP. At the same time, there is nothing in the decision that requires OFCCP to share any preliminary statistical analysis with the contractor in order to obtain this extensive amount of data.

Background of the Dispute: What Data Was OFCCP Seeking, What did Google Produce, What did Google Object to Producing

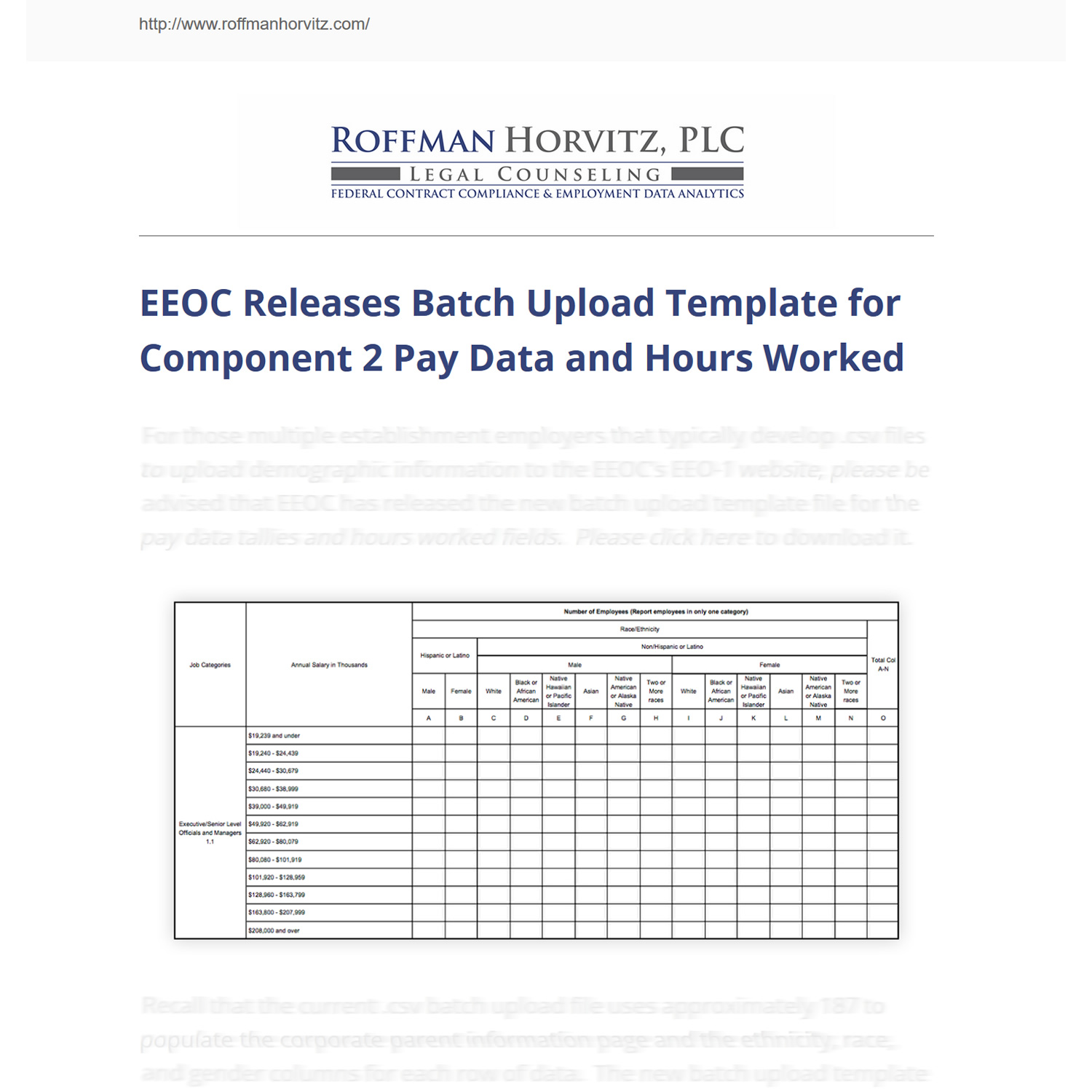

Approximately 21,000 employees work at Google's Mountain View headquarters. In response to item 19 of OFCCP's standard initial scheduling letter1, Google produced a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with the following data fields:

- Employee ID number

- Gender

- Race/ethnicity

- Hire date

- Job title

- EEO-1 category

- Job Group

- Base salary or wage rate

- Hours worked in a typical workweek, and

- Other compensation or adjustments to salary (bonuses, incentives, commissions, merit increases, locality pay and overtime).

Google produced this information on a September 1, 2015 employee snapshot to OFCCP in November 2015.

On June 1, 2016, OFCCP went beyond the OMB-approved list of pay data fields to request that Google supplement its September 1, 2015 snapshot with the following categories:

- Name

- Date of birth

- Bonus earned

- Bonus period covered

- Campus hire or industry hire (hired directly out of school or from another employer)

- Whether the applicant or employee had a competing offer

- Current Compa-Ratio

- Current job code

- Current job family

- Current level

- Current manager

- Current organization

- Department hired into

- Education

- Equity adjustment

- Hiring manager

- Job history

- Locality

- Long-term incentive eligibility and grants

- Market reference point

- Market target

- Performance rating for past 3 years

- Prior experience

- Prior salary

- Referral bonus

- Salary history

- Short term incentive eligibility and grants

- Starting Compa-Ratio

- Starting job code

- Starting job family

- Starting level

- Starting organization

- Starting position/title

- Starting salary

- Sock monetary value at award date

- Target bonus

- Total cash compensation, and

- Any other factors related to compensation.

And then on September 19, 2016, OFCCP asked for supplemental snapshot data for the following categories:

- The employees' ID [presumably to map this new data back to the other snapshots]

- Country of citizenship

- Secondary country of citizenship

- Visa (yes/no)

- Visa type, and

- Place of birth.

Google produced much of this data between August 2016 and February 2017. Google estimated that it produced 844,560 compensation data points for the 21,114 employees on the September 1, 2015 snapshot.

OFCCP then sought more information, but still at this point in the audit, OFCCP had not identified what it had found so far with all the pay data points it received. The opinion explains:

In this litigation, OFCCP seeks an order requiring Google to provide data falling into the following three categories:

- A snapshot as of September 1, 2014 – a year earlier than the first snapshot. The 2014 snapshot must address each of the 19,539 people Google employed at its headquarters on that date. It must contain the same categories of data as did the snapshot as of September 1, 2015, including all those added on June 1, 2016.

A salary history (a list of starting salary and each salary change) and job history (a list of starting job and each change in job) for each person whom Google employed at its headquarters on either of the two snapshot dates. The histories must cover the entire time Google employed each person, going back for its longest-terms employees to the founding of the corporation in 1998.

- The name, address, telephone number and personal email of every employee reflected on either the 2014 snapshot or the 2015 snapshot.

Opinion at 7-8.

OFCCP explained that it sought this additional information after it found "systemic compensation disparities against women pretty much across the entire workforce." The ALJ observed in footnote 47, though, that "OFCCP offered no evidence going to whether the disparity it found was statistically significant." Google objected to providing these additional items. In turn, OFCCP filed its administrative complaint in order to compel Google to produce these items. As such, this last request is the subject of the parties' dispute before the ALJ.

The Salient Points of the ALJ's Decision

1. Witness Credibility

The ALJ devoted a considerable number of pages in his opinion summarizing the very detailed and lengthy testimony that Google's Vice President of Compensation gave at the hearing, and the ALJ found that the VP for Compensation was a very credible witness. In contrast to the positive credibility determination that the ALJ made for Google's witnesses, the ALJ devoted nine detailed bullet points to testimony that he heard from OFCCP's Deputy Regional Director for the Pacific Region, and he was sharply critical of her testimony. Those bullet points are important because many contractors have faced frustration over the past several years that OFCCP often asks for compensation data points during a compliance review that are not relevant to how the contractor actually pays its employees. The ALJ observed:

It appears that Suhr has a vague sense – not a full and accurate understanding – of how Google sets starting salaries. She does not seem to appreciate that Google conducts a market survey for each job code in the given locality, sets a market reference point at a particular percentile on the market survey results, and determines a starting salary as a percentage of the market reference point for [] each separate job code in that locality.

Opinion at 15. At a later point in the decision, the ALJ observed:

It is evident that the questions posed to [the VP of Compensation] at the onsite failed to elicit that kind of description and that the interviewers did not entirely understand the information that they did elicit.

Opinion at 20. The ALJ lamented that both sides, in effect, were learning about each other's positions in litigation, and not earlier:

Had OFCCP made its disclosures and had Google presented [the VP's testimony] earlier, it might have made the present litigation unnecessary. Google had cooperated extensively when making disclosures earlier in the investigation. Once OFCCP gave Google the basic information about its preliminary findings, Google might have been more forthcoming with information such as [the VP's testimony about how compensation is set and administered]. Perhaps Google would have offered its own statistical analysis for OFCCP. If OFCCP understood better what Google's compensation policies are, it might have reconsidered some of its current information request. But with the information exchange occurring mid-trial, neither party could be expected to interrupt the process to resume informal discussions.

Opinion at 20.

Government contractors have been saying the same thing to OFCCP for years: Tell us what you are seeing in the data, and let us respond to what you are seeing, instead of responding to a fishing expedition. The ALJ continued:

I am not deciding that OFCCP's investigation is at a close or that OFCCP will not at some point be entitled to information other than the data I discussed earlier in this decision. But OFCCP has neither offered anything sufficient to refute [the VP of Compensation]'s testimony or shown how its theory has any grounding in Google's practices. Despite having several investigators interview more than 20 Google executives and managers over two days and having reviewed over a million compensation-related data points and many hundreds of thousands of documents, OFCCP offered nothing credible or reliable to show that its theory about negotiating starting salaries is based in the Google context on anything more than speculation... The record shows that OFCCP has not taken sufficient steps to learn how Google's system works, identify actual policies and practices that might cause the disparity, and then craft focused requests for information that bears on these identified potential causes. Without this, the requests become unreasonable: unfocused, irrelevant, and unduly burdensome.

Opinion at 38.

Yet, for all his criticism of OFCCP's lack of understanding of Google's position, the ALJ awarded OFCCP most of what it asked for. The conclusion for government contractors is that it does not matter whether OFCCP's basis for requesting the information is factually grounded, mathematically correct, or legally sufficient. It does not matter if the requests are unreasonable, unfocused, or unduly burdensome. All they have to be is "relevant."

2. The 2014 Snapshot Data Fields

Of the list of categories and data fields requested for the September 1, 2014 employee snapshot, the ALJ ruled as follows:

- Place of birth, citizenship and vis status do not appear to be part of OFCCP's current request. If OFCCP is including these, its request for an order requiring them is denied. The information exceeds OFCCP's authority and is not relevant to the characteristics that Executive Order 11246 protects.

- OFCCP has withdrawn the request for "any other factors related to compensation." Google is not required to respond to a request that is so unfocused.

- As to OFCCP's demands for department hired into, job history, salary history, starting compa-ratio, starting job code, starting job family, starting level, starting organization, and starting salary, Google "need not include this information in the September 1, 2014 snapshot."

- There is no relevance in OFCCP's request for each employee's date of birth. Age discrimination is not an area of enforcement within OFCCP's authority.

- The request for locality information is unduly burdensome because the single defining characteristic of all employees is that they worked at Google's Headquarters.

3. Personal Contact Information on 25,000 Employees

As to personal contact information on all 25,000 employees across both snapshots, the ALJ found that anecdotal information (that is, testimony) obtained from employees is relevant to OFCCP's systemic adverse impact investigation. But he was sharply critical of OFCCP's inability to explain how the information on so many employees would be protected from intrusion or hacking. He also expressed serious concerns about the employees' privacy interest:

An Order from the Department requiring these disclosures is all the more burdensome on individual employee because the employees are given no due process. These are 25,000 people whom no one has told their personal contact information might be given to the federal government, when the government has already collected (for most of them) information on their reportable (to IRS) income at work and their place of birth, citizenship and visa status, among other data points. These people have been given no opportunity to "opt in" or "opt out" of any disclosure; the decision will be made without notice and opportunity to be heard. OFCCP sees its role as protecting workers' rights, yet it has done nothing to ask if any of Google's employees objects to the disclosure. Nor does OFCCP appear to have considered whether it can gather the same relevant information without contact information for all 25,000 employees, and do this without sacrificing the goal of hiding its informants in plain sight.

Opinion at 31-32.

Despite this point, the ALJ merely ordered OFCCP to reduce its request to 5,000 employees instead of 25,000 employees. Google will produce the contact information on them, and OFCCP can contact those 5,000 employees to conduct interviews. After OFCCP has conducted those initial interviews, OFCCP may then request contact information for follow-up interviews for up to as many as 3,000 additional names. We suspect OFCCP is going to contact most of the employees by email and use a survey-like document to get answers to questions about Google's pay practices. Perhaps it will gauge the employees' willingness to be interviewed by phone or in person, and then proceed along those lines.

The ALJ ordered OFCCP to proceed very carefully, and under specific direction from the Department of Labor's lawyers in the Solicitor's Office, insofar as interviews of manager-level employees is concerned.

Whether OFCCP plans to conduct 5,000 or 8,000 interviews -- we remain troubled by how all 21,000 or 25,000 employees included in Google's headquarters location could be "similarly situated" for purposes of such an expansive data request.

It certainly is distressing for employers to read that the ALJ acknowledged the importance of the concept of "similarly situated," and further acknowledged that the principal OFCCP onsite investigator's testimony "reflected little understanding of Google's organization," yet would not address why OFCCP was entitled to a tremendous amount of information on 25,000 employees, who obviously are not all similarly situated, when OFCCP's entire model might have been flawed: "If OFCCP misunderstood Google's organization – as it appears that OFCCP might have – it is likely that OFCCP's model lacks precision when defining which employees are similarly situated for comparison and statistical analysis. That raises questions about the validity of OFCCP's analysis, but as I said, I do not reach that question. Instead, I will conclude that greater collaboration and conciliation would be helpful." Opinion at 17, n. 62. It seems that the ALJ is saying that in retrospect the dispute might not have needed to go so far in litigation had the parties been able to agree on who was similarly situated. Indeed, it is odd that this dispute is focused only on the depth (amount of information) of OFCCP's requests and not the breadth (the entire workforce covered by Google's affirmative action plan) of the investigation.

4. Salary Histories

As to salary histories, the ALJ denied OFCCP's demand to go back 19 years:

"If OFCCP wants to correct Google's policies going forward while compensating adversely affected employees who worked for Google during performance of the [relevant government contract], it need not look back 19 years to 1998. It can achieve the same ends going back far fewer years. The provision in the Compliance Manual allowing OFCCP investigators to look back more than two years only when a potential continuing violation is at issue does not imply that OFCCP investigators can look back across decades. If policies are adversely affecting current employees based on sex, OFCCP should be able to establish that for a large proportion of all affected employees by looking back three or four years."

Opinion at 40. The ALJ left it open for OFCCP to go back further than two years if it finds discrimination, consistent with its theory, based on the information it obtained, or perhaps conciliate with the contractor and arrive at a resolution, but was doubtful that OFCCP could enforce a request that went back 19 years.

Conclusion

Government contractors need to make sure they have a thorough understanding of their compensation practices. The more that compensation decisions are made uniformly pursuant to policies that are followed, without exception, the less likely OFCCP needs to come on site and interview multiple managers to understand how compensation works at each organization. Google's compensation practices were set out, in detail, on pages 10-11 of the ALJ's opinion, and are worth a close read by anyone at your organization who is in charge of compensation. Organizations that continue to ask new hires about their current salaries do so at their peril because it opens them up to adverse impact in hiring claims like OFCCP's allegations against Google.

Contractors are well-advised to conduct thoughtful, privileged analyses of their compensation data before OFCCP does an audit. Contractors also should put considerable thought to assess which of its employees it would consider similarly with respect to pay. If anything, our experience is that employers do not draw narrow enough distinctions in this regard, which, perhaps more than any other single thing, can have negative consequences for the compensation review component of an OFCCP audit. Regardless, if the whole idea is to ensure pay equity by gender and by race, employers should be getting ahead of this issue, not waiting to resolve it in full view of an equal opportunity enforcement agency.

In addition, the issues in the Google matter raise some strategic matters that employers should consider:

- Would it have been more advantageous for Google to focus its challenges on the breadth of OFCCP's investigation as covering employees who are not similarly situated rather than the depth of the information that OFCCP sought?

- Given the ALJ's order to allow OFCCP to request and obtain from Google the personal contact information of 5,000 (and perhaps as many as 8,000) employees, would Google have been better off if it had worked with OFCCP to coordinate the logistics of the employee interviews? Perhaps it could have negotiated interviews with a significantly smaller sample of its employees and done so without the need to furnish its employees' personal contact information to OFCCP.

- Does it make sense for an employer with a single location of over 20,000 employees to instead seek to prepare functional affirmative action plans, which could potentially result in more manageable-sized affirmative action plans and in turn more manageable-sized OFCCP compliance reviews?

OFCCP generally has had great success in both administrative and federal court litigation in establishing its broad authority to obtain employer data during its compliance reviews. This most recent ALJ decision in the Google matter continues that pattern. It most often will be beneficial for employers to try to work with OFCCP to develop common-sense limitations on any OFCCP requests that seem overbroad. Notably, the ALJ even suggested that both Google and OFCCP would have been better off in this matter had there been better collaboration and disclosure by and between the parties before the matter proceeded to litigation. The ALJ further commented that doing so also would be in line with the obligation by both parties to pursue "conciliation" over any disputes in a compliance review.

Under the Paperwork Reduction Act, a federal agency must receive clearance from the Office of Management and Budget ("OMB") whenever it makes a standardized data collection request of 10 or more respondents within a 12-month period. OFCCP has received OMB approval to include a 22-item information request with its compliance review scheduling letters. Item 19 of the 22 pertains to compensation data. If any agency wishes to seek information beyond what is approved by OMB, the request needs to be tailored specifically to unique information it learns after the first wave of OMB-approved data. If OFCCP were to issue the same follow-up requests to employers regardless of anything it observed in the employers' data, then that follow-up request arguably would be a standardized data collection requiring OMB's advanced approval.

Frankly, we were somewhat surprised that the ALJ found age not to be relevant or that OFCCP was not arguing that it was relevant. Although age discrimination is not an area of enforcement within OFCCP's authority, age is a common variable that can be used loosely as a proxy for experience. Because time away from the workforce can affect pay, it is not a perfect variable; but it is still a useful proxy.

Download PDF of Client Update